This week I published a massive research briefing on the health consequences eviction has on Black women and children. I’m featuring an excerpt below because publishing the entire thing makes it too long for email. To read the full thing, head over to New America’s website.

The Reality: Black women and children are the most at risk for eviction

While 2.7 million households receive an eviction filing annually, when all the people living in those homes are accounted for, the number of individuals threatened with eviction jumps to 7.6 million, and the number of those evicted via court order jumps to 3.9 million—a breathtaking leap highlighting how many people are potentially crushed under the weight of America’s housing crisis.

The key word, however, is “households.” Before new data from Princeton University’s Eviction Lab was released this fall, only household figures were calculated since court filings for formal evictions only list the names of those on the lease. This resulted in an incomplete picture of who is most impacted by evictions in the U.S. Now, using data from the Census Bureau, the Eviction Lab has shown that the demographic most at risk of experiencing an eviction in the U.S. are children—specifically Black children and their mothers. The Eviction Lab worked with the Census Bureau to probabilistically link the names and addresses on eviction filings with respondents to the 2006-2015 American Community Survey. Using this information, the Lab took a remarkably uninformative document—the formal court filing—and crafted a more fully fleshed-out profile of who receives eviction filings.

More than half of households that receive an eviction filing have a child living within the home, and nearly 33 percent of the population threatened with a filing is under the age of 15. Further, more than 10 percent of children under the age of five live in rental households threatened with an eviction each year, and 5.7 percent are evicted. Black children are especially at risk: the study found that more than 25 percent of Black children live in rental households that receive an eviction filing. For Black children under the age of five, 12.4 percent experience an eviction every year.

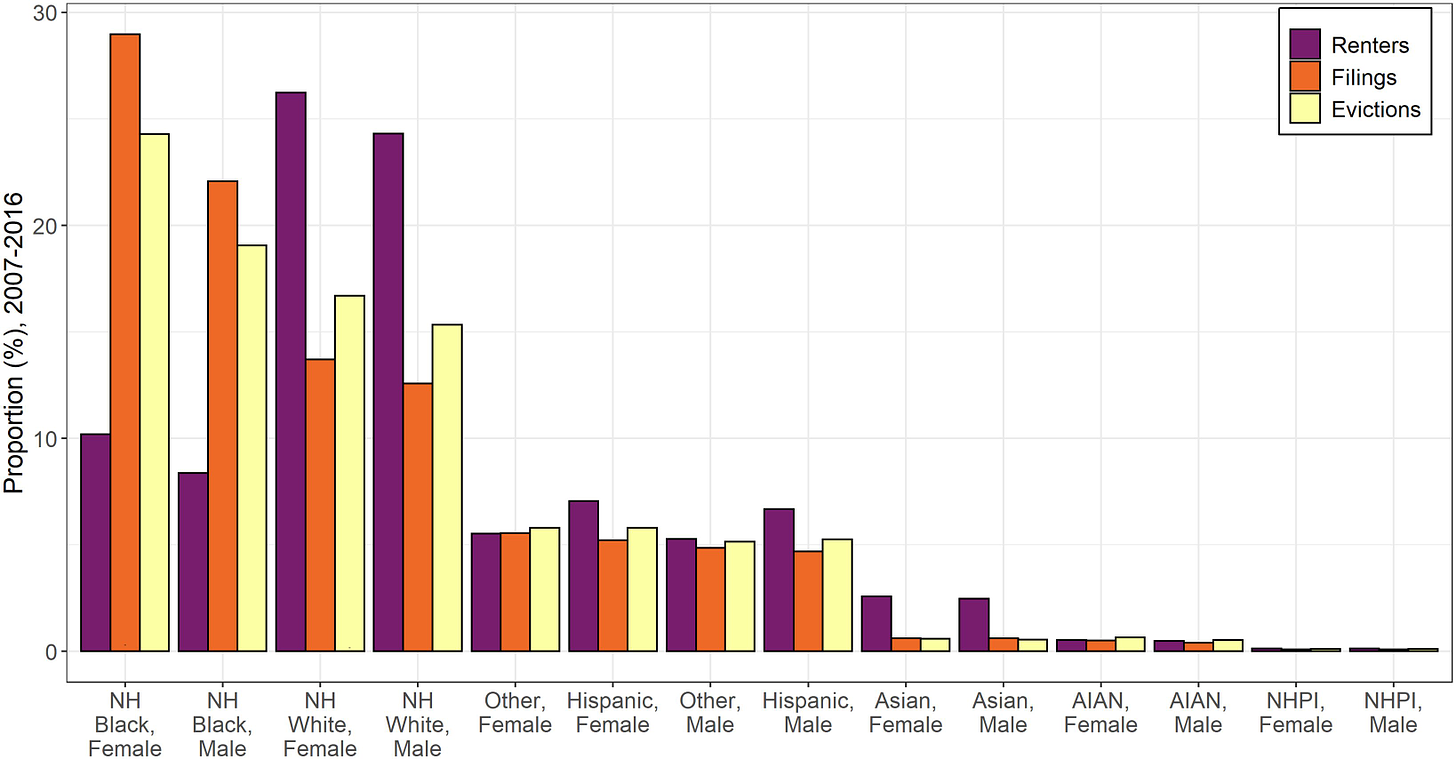

“Over 50 percent of eviction filings in this country are against a Black family,” said Carl Gershenson, the director of the Eviction Lab and one of the co-authors of the report, in a sit-down interview with New America’s Better Life Lab and the Future of Land and Housing teams.

Black renters comprise 18.6 percent of America’s renter population, yet they make up 51.1 percent of those affected by an eviction filing and 43.4 percent of those evicted nationally. Within this demographic, Black women with children are the most vulnerable, comprising 28.3 percent of the average annual rate for eviction filings and 12 percent of those evicted via court order—the highest of any other group.

Contrary to common assumptions, yearly income doesn’t explain the vast difference in eviction risk for Black households and white households. The eviction risk for Black households earning more than $80,000 is still higher than it is for a white household earning under $20,000 a year. This disparity aligns with other disparate outcomes for Black Americans that do not improve as socioeconomic status rises—such as maternal mortality, debt burden, and experiencing police violence.

“We have in our data families earning over $100,000 a year—Black families—who are still evicted. That just does not happen in white neighborhoods,” said Gershenson. “That’s almost impossible to observe in a white neighborhood and happens with some regularity in Black neighborhoods.”

While income doesn’t offer an answer to this disparity, anti-Black racism certainly does. America’s eviction crisis and how it harms Black families is a direct result of centuries of racist policies that successfully undermined our communities.

Before Eviction Lab’s data was released, I reported on eviction diversion programs in my work at the Better Life Lab—mainly how they affect Black women's and children's health. When it comes to the myriad of health risks that uniquely affect Black folks, especially women and children, eviction falls under the radar because it is routinely viewed as a housing problem, even though access to adequate housing is a social determinant of health and well-being. Below is an overview of the stakes for Black mothers and children who suffer under the racist thumb of America’s eviction crisis, the health consequences of experiencing such a disruptive life event during childhood, and potential, non-exhaustive solutions based on widely available data and research.

This compilation reveals America’s eviction crisis as a public health emergency that must be addressed using a health equity lens.

History tells us why Black mothers and their children are the demographic most likely to be evicted

Economic disenfranchisement. Unpaid rent is the cause of most eviction filings and court-ordered evictions. For Black moms, this creates a compounded financial burden: Not only are Black mothers more likely to be evicted, but 68 percent of them are their household’s sole or primary breadwinner. This earning obligation coincides with being on the short end of the racial wealth and pay gaps. Full-time working Black women earn 67 cents to the dollar as compared to their white, non-Hispanic male counterparts. This limits the amount of money available for rent and affects any chance of building longer-term financial safety nets—such as an emergency fund to weather job losses. According to the Urban Institute:

Black households have just 15 percent of the wealth of white households, and this has not changed much over time. For Black women, the gap is also stark. For instance, single Black women household heads with a college degree have 38 percent less wealth ($5,000) than single white women without one ($8,000). Among married women who are the head of the household, Black women with a bachelor’s degree have 79 percent less wealth ($45,000) than white women with no degree ($117,200) and 83 percent less wealth than those with one ($260,000). Marital status and education do not close the gap.

Racist policies. Racist policies historically target and disenfranchise Black families. An investigation by WNYC found that high eviction rate patterns follow the path of the Great Migration. “The great northern migration is a major way station on the road to today's eviction crisis—and the interrelated racial wealth gap,” said journalist Brooke Gladstone. “The net worth of the typical Black household is just 15 percent of the typical white one, and the gap is growing.”

As Black Americans fled the Jim Crow policies that dominated the South, rampant racism stayed tight on their trail. Nationwide, Black folks were barred by local officials from participating in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. Agricultural and domestic workers couldn’t draw social security benefits, a guideline that disproportionately targeted Black Americans. The same officials lobbied to ensure these occupations were excluded from the codes of fair competition—a measure enacted under the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act that fixed wages within industries—meaning Black Americans, by and large, did not receive the new minimum wages set under the New Deal. Other industries, such as restaurants, simply fired Black folks before paying them more. When the Federal Housing Administration was established in 1934 to boost homeownership, the agency wouldn’t insure mortgages for homes in or near Black communities—a policy known as redlining—which thwarted Black homeownership. Further, Black Americans were denied the educational opportunities and low-cost loans afforded to their white counterparts under the G.I. Bill.

This medley of racism prevented Black Americans from accessing one of the surest ways to build and maintain wealth: owning a home.

Racist policies specifically targeting Black women and children. American social systems have always preyed on Black mothers—particularly at the intersection of housing and other programs designed to provide socioeconomic relief. A prime example of this is “man-in-the-house” policies, which prevented mothers from receiving welfare if they were thought to be living with, or having an intimate relationship with, a single man capable of working for pay and supporting a family. (In a sick twist of American irony, the discriminations outlined in the previous section are what prevented many Black Americans from being able to support a family on a single, or even dual, household income.)

“Man-in-the-house” policies were a paternalistic way of framing social programming. The thinking was that married or otherwise coupled women shouldn’t work because men should earn enough money to support their families. So, since the underlying crux was that women shouldn’t work, qualifying single women would receive benefits so they could stay at home with their children. To enforce this rule, caseworkers would pop up at homes in the middle of the night, a practice that disproportionately targeted Black women. If a man was thought to be living in the house—a definition that fluctuated with each caseworker—the woman’s benefits were threatened. The caseworker would often deduce this based on something as ridiculous as a hat hanging in a closet or a pair of socks.

“Man-in-the-house” policies were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1968, but they set the stage for the punitive measures currently used to regulate housing. According to research from sociologist Rahim Kurwa, housing voucher regulations—like the prohibition of unauthorized residents—are an extension of this policy. According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), misrepresenting family composition, which can entail having an “unauthorized resident” living in the home, is, at best, considered an omission by the resident and, at the most extreme, is considered abuse or fraud. Any distinction between intentional and unintentional misreporting of family composition is the responsibility of the relevant public housing agency. (Such a policy not only imposes on the personal lives of people living in public housing but also aligns the housing and criminal justice systems, argues Kurwa.)

Complaints about unauthorized residents can possibly lead to eviction via “immediate termination” from a voucher program. “The subjects of these complaints are often Black women,” writes Kurwa, “and the resulting evictions compound patterns of racial segregation.”

Evictions are a direct cause of adverse health outcomes for Black children and their caregivers

Health consequences. Evictions upend a family’s sense of stability and predictability—two factors necessary for children to thrive—and stable housing is critical to healthy childhood development. Disruptions due to eviction can lead to low birth weights, premature births, poor cognitive development, infant mortality, and heightened food insecurity. When we consider the Eviction Lab’s data that evictions disproportionately affect young Black children, a demographic that is already more likely to experience adverse health outcomes as infants and as they age into adults, the long-term health effects of eviction on Black Americans become more salient.

“Eviction often leads to residential instability, moving into poor quality housing, overcrowding, and homelessness, all of which [are] associated with negative health among adults and children," according to researchers at Boston University’s School of Public Health.

There’s a clear connection between adversity in childhood and increased risk for a range of adverse health consequences during adulthood. The first 1,000 days of a child’s life— from the time of conception to two years old—is a period of significant development for the brain, body, and immune system. Any stress or instability during this time can affect the baby and their future.

Maternal stress can lead to reduced brain activity in infants. Kids who are exposed to high levels of psychological stress, including “toxic stress,” have a higher risk of contracting common childhood diseases. When these children age into adulthood, they’re met with an increased chance of developing diabetes, heart disease, various cancers, depression, substance abuse disorders, and other mental health conditions—adverse health outcomes that Black people are more likely to experience anyway. Children who have been evicted are also hospitalized more during childhood than children who have never experienced an eviction.

The “vicious cycle” of poverty. Then, there’s the aftermath of an eviction. Families attempting to find their footing and secure housing post-eviction can lead to evicted tenants forgoing medical care, food, or climate-appropriate clothing, according to sociologists Rachel Kimbro and Matthew Desmond, the founder and principal investigator of the Eviction Lab. Mothers employed at the time of eviction are more likely to be laid off or fired due to juggling multiple stressors and, understandably, choosing to focus on securing housing instead of their daily work duties.

Being evicted is a driver of poverty and multiple circumstances that foster poor health.

Interactions with punitive social systems. An eviction can open the door for child protective services to remove children from their parents’ care, for instance, as well as potentially lead to harmful interactions with armed law enforcement. Across the country, various city marshals, sheriff’s offices, and other armed law enforcement officers handle removing people from their homes. It’s well-documented what public health risks exist for Black families when they interact with police forces, including, but not limited to:

Increased risk of death or injury via police violence.

Worsened mental health and increased levels of stress among parents and caregivers.

Increased risk of preterm birth when police violence happens in the neighborhood where the pregnant person lives.

Increased levels of economic hardship and adverse health outcomes.